Welcome to the Theosophical Society

The Society

The Theosophical Society in America is a section of the worldwide Theosophical Society, founded in New York in 1875, with its international headquarters at Adyar, Chennai (Madras), India. The American Section has its national center in Wheaton, Illinois, on a beautiful forty-acre estate called Olcott in honor of the Society’s co-founder and first president, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott.

The Theosophical Society in America

- Has a Vision of wholeness that inspires a fellowship united in study, meditation, and service.

- Has a Mission of encouraging open-minded inquiry into world religions, philosophy, science, and the arts in order to understand the wisdom of the ages, respect the unity of all life, and help people explore spiritual self-transformation.

- Has an Ethic holding that our every action, feeling, and thought affect all other beings and that each of us is capable of and responsible for contributing to the benefit of the whole.

Learn More

Three Objects

No acceptance of particular beliefs or practices is required to join the Theosophical Society. All in sympathy with its Three Objects are welcomed as members. These Three Objects are:

1. To form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity, without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste or color.

2. To encourage the comparative study of religion, philosophy, and science.

3. To investigate unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity.

These Objects form the foundation for the work of the Theosophical Society (TS). Nevertheless, they can be interpreted on many levels.

The word brotherhood in the first Object is used without reference to gender. The brotherhood is also a sisterhood. This Object aims at offering a space for people to come together and share their search for Truth, regardless of any external differences. In fact it encourages us to see external differences as enriching our human experience instead of being sources of intolerance and war.

The Second Object encourages research into this truth of our unity. It thus encourages a comparative study of three different avenues humanity has taken toward the understanding of life: religion, philosophy, and science. The Society was thus the first organization in modern times to promote interfaith activities systematically and worldwide. One of its first aims was to bring to the West the wisdom of the East, at a time when non-Western religions were derided as mere superstitions.

Thanks to the work of the TS, words from the Eastern traditions, such as karma, yoga, and many others, have become known to the general public. The Society was also the first organization working to bridge the gap between science and spirituality in a time when they were regarded as absolutely incompatible.

Finally, the Third Object encourages us to investigate what has sometimes been called the “hidden side” of life and of human beings. Theosophy holds that it is very important to learn about the deep purpose of life and the spiritual laws that guide our evolution, and also to discover how to awaken to the spiritual potential that lies in every one of us. This is the only sure foundation to peace within ourselves and on earth. We cannot attain real harmony and cooperation merely through politics and social reform (though these may be necessary), but through the transformation of the human heart and mind.

If you are in sympathy with these Objects and want to share your quest for Truth with like-minded people, you can join the Theosophical Society by clicking here.

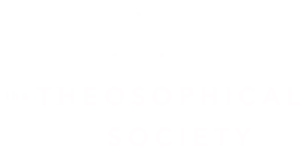

The Theosophical Society was founded in late 1875, in New York City, by Russian noblewoman, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, and an American attorney, Colonel Henry Steel Olcott, along with another attorney, William Quan Judge, and a number of other individuals in search of the Ancient Wisdom.

Mme. Blavatsky was the first Russian woman to be naturalized as an American citizen. As a young woman, she traveled all over the world in search of wisdom about life and the reason for human existence. Eventually, Blavatsky brought the spiritual wisdom of the East and that of the ancient Western mysteries to the modern West, where they were virtually unknown. Her writings became the first exposition of what is today known as modern Theosophy.

Colonel Henry S. Olcott, a prominent lawyer and journalist, became the first president of the Society. He was a veteran of the Civil War, during which he had been a special investigator into corruption in the armed services. Later he was a member of the commission appointed to investigate the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. He was also an internationally renowned agricultural authority. Olcott related the timeless wisdom of Theosophy to the cultures of both East and West, applied it to everyday life, and built the Society into an international organization.

Colonel Henry S. Olcott, a prominent lawyer and journalist, became the first president of the Society. He was a veteran of the Civil War, during which he had been a special investigator into corruption in the armed services. Later he was a member of the commission appointed to investigate the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. He was also an internationally renowned agricultural authority. Olcott related the timeless wisdom of Theosophy to the cultures of both East and West, applied it to everyday life, and built the Society into an international organization.

In 1879, Blavatsky and Olcott, the principal founders, moved to India, where the Society spread rapidly. In 1882, they established the Society‘s international headquarters in Adyar, a suburb of Madras (currently Chennai), where it has since remained. They also visited Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka), where Olcott was so active in promoting social welfare among oppressed Buddhists that even now he is a national hero there.

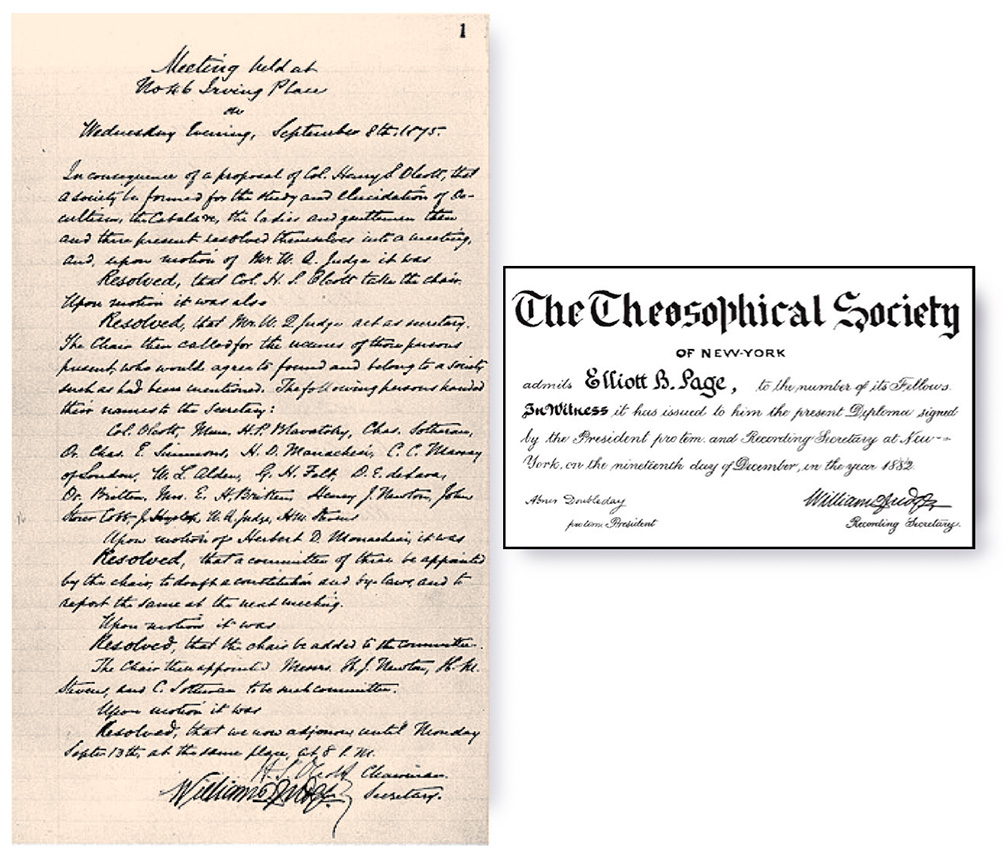

By 1886 William Q. Judge had established an American Section of the international Society comprising branches in fourteen cities. Rapid growth took place under his guidance, so that by 1895 there were 102 American branches with nearly 6000 members. It was legally renamed The Theosophical Society in America (TSA) in 1934, and exists under that name to this day.

The administrative center of the TSA (called “Olcott” in honor of the co-founder) is located in Wheaton, Illinois, on forty acres of grounds. Olcott’s offerings include an extensive library, a bookstore, and a wide range of lectures and programs by many different authorities. Approximately 110 local groups in major cities of the country carry on active Theosophical work as well.

Today the international TS has members in almost seventy countries around the world. The Society was influential in the creation of many later esoteric movements, a number of which were founded by former TS members. Some notable cases are Dr. Gérard Encausse (Papus), founder of the modern Martinist Order in France; William W. Westcott, cofounder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in the U.K.; Max Heindel, founder of the Rosicrucian Fellowship in the United States; Alice Bailey, founder of the Arcane School; Rudolf Steiner, founder of the international Anthroposophical Society; the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich and his wife Helena, founders of the Agni Yoga Society; and Guy and Edna Ballard, founders of the I AM Movement, among others.

The Philosophy of the Society

The Society is dedicated to promoting the unity of humanity; fostering religious and racial understanding by encouraging the study of religion, philosophy, and science; and furthering the discovery of the spiritual aspect of life and of human beings.

The Society stands for a complete freedom of individual search and belief. It encourages its members to examine any and all concepts and beliefs with an open mind and a respect for other people’s understanding.

• Freedom of Thought

Any person who sympathizes with the Three Objects can join the Theosophical Society. The Society maintains the right of individual freedom of thought for every member. Nobody is asked to give up the teachings of his or her own faith. To ensure this right, the General Council of the Theosophical Society passed the following resolution in 1924:

“As the Theosophical Society has spread far and wide over the world, and as members of all religions have become members of it without surrendering the special dogmas, teachings and beliefs of their respective faiths, it is thought desirable to emphasize the fact that there is no doctrine, no opinion, by whomsoever taught or held, that is in any way binding on any member of the Society, none which any member is not free to accept or reject. Approval of its three Objects is the sole condition of membership. No teacher, or writer, from H.P. Blavatsky onwards, has any authority to impose his or her teachings or opinions on members. Every member has an equal right to follow any school of thought, but has no right to force the choice on any other. Neither a candidate for any office nor any voter can be rendered ineligible to stand or to vote, because of any opinion held, or because of membership in any school of thought. Opinions or beliefs neither bestow privileges nor inflict penalties. The Members of the General Council earnestly request every member of the Theosophical Society to maintain, defend and act upon these fundamental principles of the Society, and also fearlessly to exercise the right of liberty of thought and of expression thereof, within the limits of courtesy and consideration for others.”

• Freedom of the Society

Just as all members of the Society are free to hold their own beliefs and follow their own practices, no one can impose his or her particular views or aims on the Society, which has its own declared Objects. To ensure this freedom of the organization, the General Council of the Theosophical Society passed the following resolution in 1949:

“The Theosophical Society, while cooperating with all other bodies whose aims and activities make such cooperation possible, is and must remain an organisation entirely independent of them, not committed to any objects save its own, and intent on developing its own work on the broadest and most inclusive lines, so as to move towards its own goal as indicated in and by the pursuit of those objects and that Divine Wisdom which in the abstract is implicit in the title, The Theosophical Society. Since Universal Brotherhood and the Wisdom are undefined and unlimited, and since there is complete freedom for each and every member of the Society in thought and action, the Society seeks ever to maintain its own distinctive and unique character by remaining free of affiliation or identification with any other organization.”

The Seal of the Theosophical Society

The emblem or seal of the Theosophical Society consists of seven elements that represent a unity of meaning. It combines symbols drawn from various religious traditions around the world to express the order of the universe and the spiritual unity of all life.

The Sacred Word

The Sacred Word

At the top of the emblem is the Sanskrit word Om, a very sacred word in India, being used by Hindus, Buddhists, and others. It cannot be translated into English because it has symbolic rather than ordinary meaning. It is pronounced as a single syllable, “om,” but is written with three letters in Sanskrit: a, u, and m—au being the way Sanskrit writes the sound o. It is thus the ultimate Unity manifesting itself in a threefold way. It is the trinity, which is found not only in Christianity, but in Hinduism, Buddhism, and indeed all over the globe in many religions.

As a Sacred Word, Om is like the Greek term Logos, adopted by the early Christians to symbolize the divine order manifested in the universe: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” It is the word that creates, sustains, and transforms the whole cosmos: the word eternally spoken by God.

Even the shape of the Sanskrit letters is interesting symbolically. What looks like a “3” connected to what looks like the Greek letter pi is the Sanskrit letter a, which is thus written in two dimensions. The small curved line over the pi-like part of the letter a is the letter u, which is one dimensional. And the small dot is the letter m, having no dimensions. As the letters of the word Om progress from one to the next, they become smaller in dimensions, finally ending with the primal point, the singularity from which the whole universe expands at the time of the Big Bang.

The Om is at the top of the seal because it symbolizes the Absolute expressing itself as the three-in-one divine intelligence or Logos from which the universe emanates and to which, at the end of time, it returns. The great Hindu devotional work, the Bhagavad Gita, says that the word Om should begin everything, because it symbolizes the divine origin of all things.

The Whirling Cross

The Whirling Cross

Below the word Om is a whirling cross within a circle. It is a very ancient symbol, found all over the world—in India, among American Indians, and in many other cultures around the globe. In Sanskrit it is called a swastika, meaning “good.” It comes from the word swasti “welfare,” in turn from su “well” and asti “it is.” In popular use in India, it is thought to be a sign of good luck. In medieval Europe it was used by Christians and called a gammadion (because it is made of four Greek gamma letters) or in England a fylfot because it was used as a design to fill (fyl) the foot (fot) of stained glass windows.

The Nazis adopted this ancient holy symbol (which they called Hakenkreuz or “bent cross”) and perverted its meaning, much as the Ku Klux Klan in the United States adopted the cross and perverted its meaning as a sign of hate and intimidation. But the swastika is still used as a holy symbol all over the world, for example by the Jains of India, whose religion is devoted to harmlessness.

All crosses symbolize some aspect of manifestation. The swastika is a whirling cross, its clockwise (righthanded, sunwise, or deasil) motion suggesting the dynamic forces of creation. So the swastika represents the great process of becoming, which produces the world in which we live. It symbolizes what astrophysicists call the expansion of the universe. When the swastika is represented as turning in the opposite direction (that of the Nazi Hakenkreuz), it symbolizes the forces of contraction or destruction that bring about the end of a world when it has completed its evolution. The reverse turning swastika is not evil, but merely a symbol of the winding up of creative energies and of the process of coming to an end.

The circle that encloses the swastika is what is called the “ring-pass-not,” that is, the boundary around our universe and within which the creative forces constantly swirl and evolve life. The center of the whirling swastika, however, is still. When we are there, we are, as T. S. Eliot said in Burnt Norton, “at the still point of the turning world.” It is the point of calmness and peace in the midst of the constantly changing world all around us.

The encircled swastika, symbolizing the world in its dynamic aspect of becoming, is just below the Om symbol, which represents the eternal and absolute from which the world emanates. Their arrangement in the seal is therefore meaningful. This changing world depends on or hangs from the unchanging absolute. Moreover, the rest of the seal, which represents particular aspects of this evolving world, expands from the encircled swastika. The rest of the seal gives us, as it were, a closer look at the process symbolized by the whirling cross, the process going on within it.

The Ouroboros

The Ouroboros

Immediately connected with the whirling cross is a serpent swallowing its own tail. This symbol was called by the ancient Greek Gnostics and alchemists ouroboros. The circle it forms is a restatement of the circle around the swastika, representing the boundary of the universe, and the fact that it passes through the encircled swastika suggests that the serpent and everything it encircles are part of the creative energy of the whirling cross.

The serpent swallowing its tail also represents the cycles of nature, the bounded eternity of the world, and the infinite order of life. One of the ideas it suggests is that which T. S. Eliot expressed in his poem East Coker: “In my beginning is my end,” that is, law and orderliness are to be found everywhere in the universe and in human life, so the end of everything is implicit in its beginning.

In the West, the serpent or the dragon is sometimes interpreted as a symbol of evil or temptation, but in the East, it is generally a symbol of wisdom, longevity, and happiness. In China, the dragon or winged serpent is a very favorable figure. In the Hindu tradition, the nagas or serpents are guardians of the good, and holy men are called “nagas.” Even in the West, the serpent is associated with wisdom; Christ advised his followers to be “wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.”

The serpent is also a symbol of healing, that is, of wholeness. Moses cured the sick among the Children of Israel in the desert by having them gaze upon a fiery serpent set upon a pole. Christian Church fathers interpreted that serpent as a type or anticipatory symbol of Christ on the cross. And one or two serpents intertwining a staff are even today a symbol of the healing professions. The fact that the serpent sheds its skin each year makes it an emblem of the cyclical process of the world and of the renewal of life, that is, of resurrection. And so in that way again the serpent is an analog of Christ and of the transformative process we will all pass through.

The Two Triangles

The Two Triangles

The area inside the serpent’s circle represents the whole universe and everything in it. In colored versions of the seal, it is usually blue, passing from a light sky or baby blue at the top to a dark, almost navy blue at the bottom. That blue represents the cosmic sky, not just the physical sky we see, but the whole range of material substance in the universe, from rarefied, subtle matter at the “top” of the universe to gross, dense matter at the “bottom.” This colored background is not really a part of the seal, but it lends its own meaning to the whole symbol, as do the various other colors used in some versions of the seal.

Upon that background of the universe are two interlaced triangles, another worldwide symbol. The hexagram or six-pointed star that they form is universal and has many meanings. It is found in Judaism as the Seal of Solomon or the Shield of David (magen david), but the symbol is also found in India, among the Gnostics and alchemists, and elsewhere around the world.

The upward-pointing triangle, which is light in color, symbolizes spirit or consciousness. The downward-pointing triangle, which is dark in color, symbolizes matter or substance. The fact that the two triangles are interlaced is a statement of the interdependence of spirit and matter. It is a basic Theosophical concept that every particle of matter has consciousness in it and that every spark of consciousness functions through a material form. Matter and spirit are mutually dependent. Neither can exist without the other.

The idea that matter and spirit are the two sides of one coin is reflected also in traditional Christian theology. It holds that at the end of time there will be a “general resurrection,” when all dead bodies will be brought to life and united with the souls from which they were separated at the moment of death. So in eternity, Christian theology says, our souls and bodies will again be conjoined, just as they now are. The inner meaning of the Christian doctrine of the last, general resurrection is the same as the Theosophical teaching of the mutual coexistence of matter and spirit. Reality is a whole, a unity expressing itself as both spirit and matter while remaining essentially One. That fact is expressed by the interlaced triangles, which, although two, form an interrelated whole just as spirit and matter or consciousness and substance do.

It is significant that triangles rather than some other geometrical shape are used to symbolize spirit and matter. Spirit and matter are both threefold in their natures. Spirit or consciousness has three aspects: the reality of being, awareness of others, and joyful activity. In Hinduism those are called sat (being), chit (awareness), and ananda (bliss), three terms often run together as sat-chit-ananda to symbolize the unity of these three aspects. In Platonic philosophy they are called the Good, the Beautiful, and the True. In Freemasonry they are called Wisdom, Strength, and Beauty. In Christianity they correspond to the three divine Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and to the three supernatural virtues: faith, hope, and love.

Matter likewise has three aspects: stability, activity, and regularity. In Hinduism they are spoken of as three “strands” (gunas) out of which matter is woven: tamas or inertia, rajas or activity, and sattva or harmony. They correspond to the three alchemical elements of salt, mercury, and sulfur, and are represented by the three colors black, red, and white (or dark, bright, and light), which are the basic colors found all over the world.

So it is not accidental that triangles are used to represent both spirit and matter. The three sides and three points of the two triangles total twelve, the number of the signs of the Zodiac, the Tribes of Israel, the apostles of Christ, the labors of Hercules, and a lot of other mythological and symbolic dozens. They all refer to the experiences we go through in this world.

The Ankh

The Ankh

At the center of the six-pointed star of spirit and matter is the Egyptian cross or ankh, symbolic of life. The six points of the triangles and the ankh at the center represent the seven principles of the universe. Or, if we think of the hexagram as having twelve sides or twelve points (six outward and six inward), the center is the thirteenth element, corresponding to Christ among the apostles, Hercules in his labors, and so on. The ankh also represents the idea that life results from the interaction of spirit or consciousness (the upward triangle) and matter or substance (the downward triangle).

The ankh is also called an “ansate” cross, that is, a cross “with a handle.” Human or divine figures in Egyptian art are often depicted as carrying the ankh by its loop or “handle.” When we are functioning in a fully human mode, with spirit and matter balanced, we have, as it were, a “handle” on life.

Since the ankh consists of a tau (or T) cross topped by a circle, it combines the meanings of the T-square and the circle. The T-square is an instrument used by draftsmen and architects to draw parallel lines (symbolically, to recognize parallelisms and analogies) and as a support for triangles in drawing angles (symbolically, for serving as the basis for all the triplicities of spirit and matter). Like all square forms, it also represents matter. The circle represents spirit. The T-square and circle combined are thus another representation of spirit and matter interacting and producing life by their interaction.

Thus the ankh repeats on a lower register the symbolism already expressed by the interlaced triangles, the serpent, and the encircled swastika. All of those elements speak of the mutual connections between spirit and matter as expressions of the divine source, symbolized by the crowning Om. The repetition, with variation in details, of the same symbolic meanings by these different elements is a statement of the correspondences that exist throughout the universe. The world finally is one and whole, it is coherent, and it is meaningful in all its parts. That is what the seal is also saying in its entirety.

The Motto

Around the bottom of the serpent is a motto: “There is no religion higher than truth.” It is an English translation of a Sanskrit motto, one word of which has special meanings that shed light on the whole motto. The original Sanskrit is Satyan nasti paro dharmah, which might also be translated as “Nothing is greater than truth.” The first three words can be literally translated thus: satyan “than truth,” nasti “is not,” paro “further, greater, higher.” Dharmah is difficult to translate because it means so many things. Its root meaning is “what is established or firm.” And from that basic root sense radiate such other meanings as “law,” “customs,” “duty,” “morality,” “justice,” “religion,” “teachings or doctrine,” “good works,” and “essential nature.”

The motto is not specifically about what we think of as religion. Instead it is saying that none of our commitments or social conventions or ideas can measure up to the reality of what truly is. Reality is greater than any of its parts and is beyond all our notions about it. In saying that, the motto at the bottom of the seal directs our attention back to the word Om at the top. That word is a symbol of what truly is, of Truth. And so the whole seal, just like the serpent, ends where it began—affirming the supreme Truth that unites all things.

National Center

Olcott is an administrative center, but it is also a place where members and the public may participate in onsite courses, workshops, and retreats, or attend lectures and seminars on a wide variety of spiritual topics. It provides a summer convention for members in conjunction with the Society’s annual meeting, usually in July, at which Theosophical students gather to learn from one another. Many of these programs have been recorded and are posted online for free viewing or listening (See Online Resources).